"Ancient Egyptian society was a masterpiece of social engineering, highly structured and hierarchical. This rigidity was not born of oppression, but of a deep metaphysical commitment to Ma'at—the cosmic principle of balance, order, and harmony."

To the Ancient Egyptians, the social pyramid was a reflection of the divine order. Every individual, from the divine Pharaoh to the humble field laborer, had a preordained role to play. Stability was believed to depend on each group fulfilling its specific duties to maintain the universal flow of life. Social hierarchy was thus religious, political, and moral all at once.

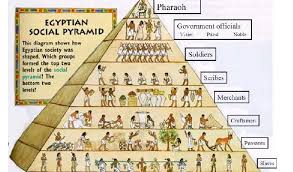

The Divine Pyramid

The structure of society mirrored the shape of the pyramids themselves, with power concentrated at the top and flowing downwards.

- The Pharaoh: At the apex stood the King, the living Horus. He was the only person who could communicate directly with the gods. His duty was to uphold Ma'at by defending the borders and maintaining the temples.

- The Vizier & Nobles: The highest officials who managed the bureaucracy, justice system, and taxation. They were the "eyes and ears" of the Pharaoh.

- The Scribes & Priests: The intellectual elite. Scribes kept the records that allowed the economy to function, while priests maintained the daily rituals that kept the gods happy.

- Artisans & Craftsmen: Skilled workers (goldsmiths, carpenters, painters) who lived in specialized villages like Deir el-Medina. They created the physical manifestations of eternity.

- Farmers & Laborers: The vast base of the pyramid. They grew the food that fueled the entire civilization. Their labor was often paid as tax to the state during the flood season.

Harmony Through Duty

This system was not viewed as exploitation but as Vertical Solidarity. The peasant fed the king, and the king protected the peasant and ensured the sun rose every morning by appeasing the gods. If one part of the pyramid failed, Ma'at would be lost, and chaos (Isfet) would return.

More Than Just Tyranny

While rigid, the system allowed for some mobility. A peasant who learned to read could become a scribe. Women, though legally dependent on male relatives, could own property, initiate divorce, and run businesses—freedoms unknown to women in ancient Greece or Rome.