Menkaure

The king who chose perfection over size, builder of the Third Giza Pyramid.

(Men-Kau-Ra: "Eternal are the Souls of Ra")

🕰️ Reign

c. 2530–2500 BCE

🏆 Monument

The Third Pyramid

📍 Location

Giza Plateau

👑 Father

Khafre

The Divine Pyramid: "Netjer-Menkaure"

Menkaure's pyramid, named "Netjer-Menkaure" (Menkaure is Divine), stands as a testament to the shift in royal ideology during the 4th Dynasty. Though significantly smaller than the pyramids of his father Khafre and grandfather Khufu (standing at 65 meters or 213 ft), it is widely considered the most beautiful in terms of craftsmanship and material value.

- The Red Granite Casing: Unlike his predecessors who used fine white limestone for the entire casing, Menkaure opted for a much harder and more expensive material for the bottom 16 courses: Red Aswan Granite. This stone had to be quarried and transported over 900 km down the Nile from Aswan, making the effort per block significantly higher than local limestone. This gave the pyramid a unique, two-toned appearance: red at the base and white limestone at the top.

- The Complex Interior: The substructure of Menkaure's pyramid is more complex than Khafre's. It features a descending passage, a panelled chamber, and a burial chamber lined entirely with granite. The arched ceiling of the burial chamber was carved on the underside to resemble a barrel vault, a sophisticated architectural feature.

- Unfinished State: The granite casing was never fully smoothed, likely due to the king's unexpected death. This provides modern archaeologists with invaluable insight into how the ancients worked stone, as the tool marks, lever bosses, and smoothing lines are still visible on the north face today.

The Lost Sarcophagus: A Tragedy at Sea

The burial chamber of Menkaure originally contained one of the most stunning masterpieces of the Old Kingdom: a rectangular sarcophagus made of high-quality basalt. It was intricately carved with the "palace facade" motif (serekh style), a detail usually found in Old Kingdom architecture but rarely depicted with such detail on stone sarcophagi.

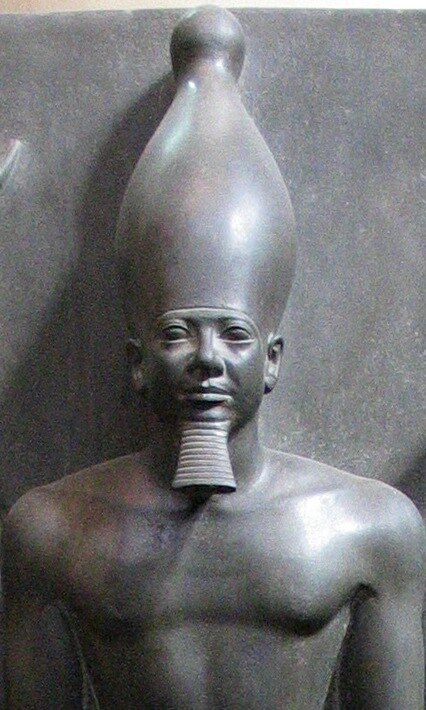

Artistic Revolution: The Masterpieces of Statuary

If Khufu is defined by the sheer size of his pyramid and Khafre by the majesty of the Sphinx, Menkaure is defined by the exquisite beauty of his statuary. Excavations at his Valley Temple by George Reisner yielded some of the finest sculptures ever produced in the ancient world, showcasing a move towards high naturalism and emotional expression.

- The Greywacke Triads: Several statues depict Menkaure standing between the goddess Hathor (mistress of the West and love) and a personification of a corrupted Egyptian Nome (province). These statues show the king as an athletic, youthful figure, stepping forward into eternity, supported by the gods. They are masterpieces of anatomical precision carved in extremely hard stone.

- The Famous Dyad: Perhaps the most famous piece is the statue showing Menkaure and his primary queen, Khamerernebty II (now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts). The queen's arm is wrapped affectionately around the king's waist, presenting them as a unified couple. It is a rare display of intimacy and equality in royal art, setting the standard for royal portraiture for centuries to come.

The Legend of the Benevolent King

History has treated Menkaure far more kindly than his ancestors. Unlike the harsh reputation of his grandfather Khufu (Cheops) and father Khafre (Chephren), who were described by Herodotus as tyrants who closed temples to force labor, Menkaure was remembered as a kind, pious, and just ruler.

Herodotus wrote that Menkaure reopened the temples and allowed the people to worship freely, relieving them of the suffering caused by his predecessors. He was considered one of the most just kings of the Old Kingdom. A famous legend says an oracle from the city of Buto predicted he would only live six years because he was "too good" for a world destined for suffering. In defiance, Menkaure lit lamps every night to turn night into day, drinking and celebrating, effectively doubling his remaining time by living day and night.

The Scars of History: The Attempted Destruction

Menkaure's pyramid bears a large, distinct vertical gash on its northern face, a scar from a deliberate medieval attempt to destroy it. In the 12th century AD, the Ayyubid Sultan Al-Aziz Uthman (son of Saladin) ordered the demolition of the Giza pyramids, starting with Menkaure's because it was the smallest.

Legacy: The End of the Giza Giants

Menkaure's pyramid marks the end of the era of giant pyramids. After his reign, the focus of royal construction shifted. The immense resources required for Giza were unsustainable. Later kings of the 5th and 6th Dynasties moved their necropolises to Saqqara and Abusir, building smaller pyramids with rubble cores but investing more in the decoration of mortuary temples and the carving of the Pyramid Texts.

The Giza Plateau was effectively "full" after Menkaure. However, his complex, with its associated queen's pyramids (G3-a, G3-b, G3-c) and his mortuary temple (which was hurriedly finished in mudbrick by his successor Shepseskaf), remains a perfect example of a royal funerary complex. It proves that greatness in Ancient Egypt was not measured by size alone, but by artistic perfection, religious devotion, and endurance.